Villa Bennet-Voronoff

This post is also available in:

Italiano (Italian)

Italiano (Italian)

Entering Italy from the western part of the Ligurian Riviera (“Riviera di Ponente”) visitors find themselves between the mountains and the sea with stimulating landscapes which many XIX travellers enthusiastically described in their accounts and diaries. The city of Ventimiglia was thus nicknamed “the entrance to the Italian garden”.

The very first place to visit is, therefore, Villa Bennet-Voronoff and its wondrous garden.

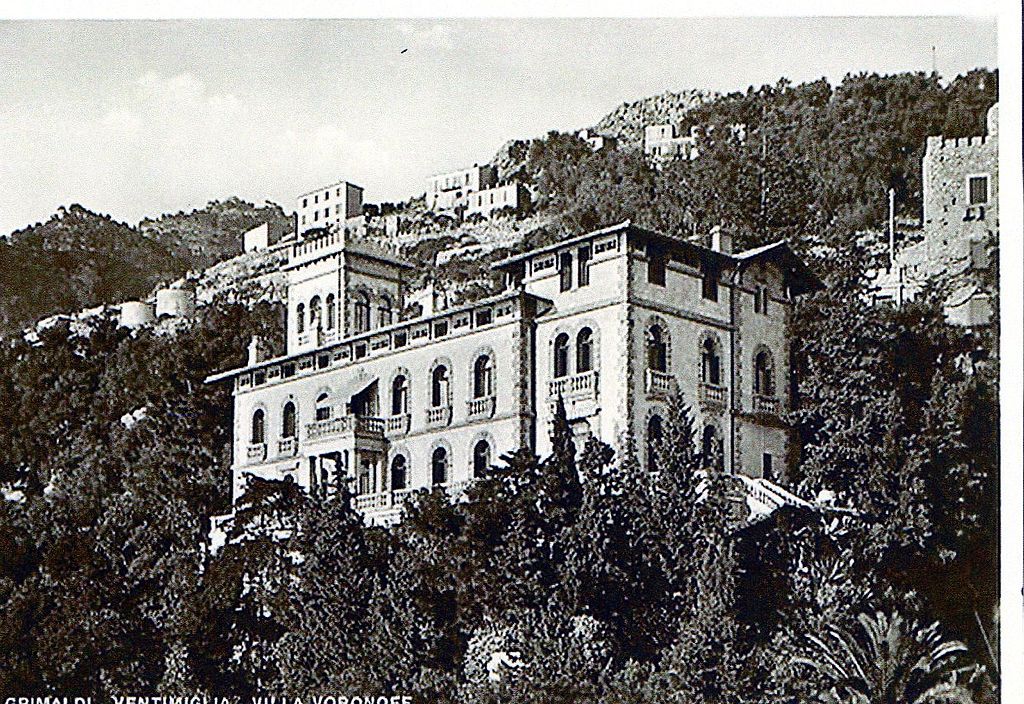

Built in the last decade of the XIX century, it had two floors and an attic with a pitched roof. On its left was the embattled Guelf tower with ten windows and a large panoramic terrace.

Above the ground floor, there used to be a portico with a balcony on the Ligurian Sea, and a central loggia-balcony with a belvedere. The back of the building featured several mullion windows with protruding terraces and an elegant porch on the ground floor with a large loggia and a view of the French and Italian Riviera.

On the right side of the villa, an exquisite external staircase led to the upper floors.

The castle with underground rooms was equipped with walls and the main entrance gate. Inside, it had a noble floor and another one for the servants and the assistants of Dr. Voronoff. On the former, there was also a well-stocked library, visitor parlours and a large rectangular dining room with two crystal walls (one facing France, the other Italy).

Art Nouveau and Russian style furnishing elements were obviously chosen.

The true protagonists of the surrounding area were orange trees, palms, Barbary figs and rose gardens – everything neatly arranged on terraces, according to the Ligurian traditions. Birds were just as abundant throughout the estate.

In 1925, Russian doctor Serjei Voronoff bought the castle and the park from a vice-consul. Voronoff was born in 1866 in Voronej, some 560 miles south of Moscow. His family were middle-class Jewish. After getting a high-school diploma, he was charged with subversion, arrested and imprisoned for fifteen days. Thus he lost faith in his Tzar, supported the peasants, while he was banned from university courses. Soon, he decided to leave Russia, and in 1885 he moved to Paris and enrolled in the faculty of Medicine. To avoid anti-Semitism hate (those were the years of the Dreyfus Affair) he went by the name of Serge.

In 1895, the young doctor was entrusted by his teacher, the famous professor Péan, with the challenge of organizing surgical services in Egypt. During his fifteen years-stay in that country, Serge proved himself a true professional and had the chance to research hormones and human ageing, as well as transplants. By doing so, he was also acknowledged as a brave pioneer with rare surgeon skills.

Voronoff could not perform transplants between individuals of the same species (sheep in particular), since the law did not allow it. Still, he was able to carry out the first “graft” (that’s how they called transplants back then) in Nice, in 1913. He actually transplanted a lobe of a chimpanzee thyroid on a boy suffering from cretinism: it was a success – or so it seemed – and the surgeon did it many times again until 1927 when hormones could eventually be synthesized in a lab.

After working on thyroids, Voronoff started experimenting with testicles and ovaries. He constantly strived to make people live much longer. In the meantime, keeping chimps as pets was getting more and more popular, especially in Europe. In 1925, when Voronoff bought the former Grimaldi’s castle (which, in our case, is erroneously translated from the French “château” – “a majestic and huge villa”) he decided to have some animal cages and a surgery lab built in the vast garden. Working on apes, he managed to perform some 2.000 transplants.

In 1936, Voronoff married his third wife – Gerty – who was 49 years younger. Two years later, he was expelled from Italy because of the new Italian racial laws. His estate was also confiscated.

Serge managed to save himself by moving to the USA. In 1946, he stayed for a while in Montecarlo and then in Bordighera. Saddened by the ruins of his former abode and its majestic garden, he decided to rebuild as much as he could, despite his old age. Two years later, along with Gerty, he was able to inaugurate the new villa – similar to the original one – and restart his research, this time on cancer.

While recovering from a fall in Lausanne, during a conference tour, Voronoff suffered severe chest difficulties and died in 1951.

This post is also available in:

Italiano (Italian)

Italiano (Italian)

Contatti

Corso Mentone, 50 - Ventimiglia(IM)

Altre info

Giardino privato. Per ogni programma di visita, occorre verificare con la proprietà le eventuali disponibilità .